Diet sheets, recipes and menus are frequently requested by people newly diagnosed with DD but there is great variation in which foods help or cause problems for different people. A strict diet is not needed other than one which has plenty of variety and fluids, and conforms to the healthy diet currently recommended for everyone. Anything which is found to cause problems should be avoided, or reduced in amount or frequency but not to the extent that diet becomes restricted. People have different tastes and food should be enjoyed.

AFRICAN DIETS

DD patients, new and old, will find that many resources recommend a diet high in fibre, some to the extent that fibre needs to be doubled in quantity with the aid of wheat bran. The fibre and bran treatment for DD started about 1970 when some doctors working in Uganda (1) found no cases of DD and attributed this to the large amount of fibre in the diet. As Mr Hutchinson described in the last Incontact magazine, too much fibre can have its own adverse effects (very high incidence of sigmoid volvulus). Was this evidence from Uganda sufficient to conclude that a low fibre diet was the cause of DD and increasing dietary fibre, and bran in particular, would both prevent and treat DD?

Dr A Weston Price (2) had also travelled in Africa and recorded native diets and health. Masai and other tribes relied on animal products such as blood, milk and meat, and had very little fibre. They also did not get ‘Western’ diseases such as DD. At the other end of the climate spectrum, Dr Sinclair (3) investigated the Inuit people who lived on fish, and meat and fat from marine mammals. They also did not get ‘Western’ diseases. Their thin blood instigated the “omega-3 Eskimo” diet to help blood circulation problems in the West (4). As in Uganda, too much of a good thing caused problems in that bleeding after accidents was a main cause of Inuit deaths. The Inuit did not get DD unless they lived in settlements and ate more fibre. The Ugandan doctors knew that DD was also rare in other African countries and also in Asia and the Middle East. They attributed this to unchanged eating habits without any reference to the amount of dietary fibre levels (1). More recent reports from Africa suggest that dietary fibre levels have dropped in urban areas without an increase in DD (5,6) In Kampala, Uganda, DD is increasing in patients still eating a traditional diet (7).

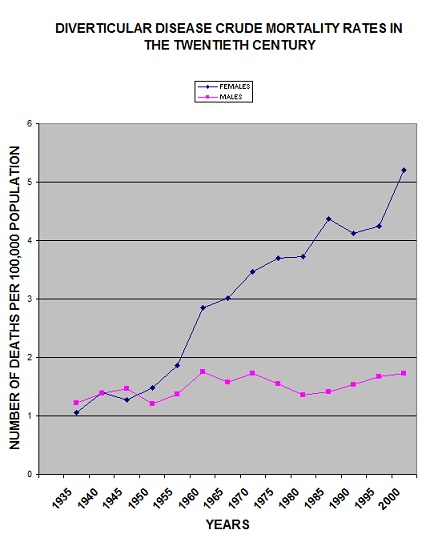

MORTALITY STATISTICS

Many promoters and supporters of the dietary fibre theory consider the ultimate evidence of validity is to be found in mortality statistics. The graph shows crude death rates for DD in the 20th century in England and Wales. Deaths from DD levelled off during the WW11, when the national loaf contained more fibre. This ‘proof’ has been accepted and quoted for nearly 4 decades. During the war years, the recording of deaths had to be reclassified to ICD5. (ICD = International Classification of Diseases) because mortality statistics were only available for civilians and were based on a reduced and biased population (8) This is a far more likely explanation. The graph also shows that the change to a high fibre diet for DD in the 1970s had no impact on mortality rates, nor can diet explain the gender difference. The aberration in results from 1990 is also due to change in recording deaths and a correction factor is available to increase the crude data.

CONTRADICTIONS

A few researchers (9,10,11,12)have disagreed with the fibre theory over the years but status, publicity and convenience continue to prevail over science. There has always been a contradiction in that a low fibre diet supposedly produced high pressures inside the colon which caused diverticula to form, but in the treatment of diverticulitis, a low fibre diet rests the colon and allows it to heal. In a similar way, the old research papers relating to fibre effects in animals and uncontrolled trials in humans give plenty of opinion but little evidence that low dietary fibre levels causes or prevents DD. A few years ago, too much sugar was an alternative theory (13). More recently (14) the role of vegetable fibre, and too much meat have been questioned by orthodox medicine. This is really an admission that after a century, we do not know what causes DD or how to prevent it. Dietary fibre is not the answer.

CONSTIPATION

On the other hand there is plenty of evidence to show that fibre in the diet can reduce symptoms caused by constipation whether this is DD or age related or both. Plant structures and contents which are not digested by the body pass into the colon and stimulate it by adding bulk to faeces so there will be more to pass and more often. Uncooked wheat bran is particularly good at producing soft bulky stools and reducing straining. Maybe it works because of its gluten content so that faeces swell up like bread dough. It can certainly feel like that sometimes and can also have unexpected efficiency. Increasing dietary fibre, with a good fluid intake, is the first, safe option to try when a person is struggling with small hard faeces. However, some people with DD do not need bran in addition to their normal diet, some people find it unpalatable and prefer other fibre options and some people take or are given too much leading to urgency, discomfort and accidents.

Constipation can have many causes e.g. medication for other complaints, enforced inactivity etc. When the bowel is not be able to respond readily to stretching of its walls then increased fibre adds to the problem and a different type of laxative would be more suitable. Fibre levels should be reduced to give the bowel less work when there is diarrhoea or the inflammation and infection of diverticulitis.

There is no “dose” of bran or fibre, or level of intake which suits everybody. As always seems to be the case with DD, personal experience is the only way to find if increased fibre is helpful and this should be based on reducing pain and discomfort and not on meeting targets, such as grams per day of fibre or bran.

REFERENCES

1 Painter NS and Burkitt. Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of western civilisation. Br Med J. 1971, 2, 4502

2 The Weston A Price Foundation. Out of Africa: what Dr Price and Burkitt discovered in their studies of sub-Saharan tribes. http://www.westonprice.org. accessed Oct. 2005

3 Sinclair HM. Essential fatty acids and chronic degenerative diseases. In Rose J ed. Nutrition and Killer diseases. 1982. Noyes, New Jersey. p69

4 Editorial. Eskimo diets and diseases. The Lancet. 1983, 3, 1139.

5 Oettle GJ and Segal I. Bowel function in an urban black African population. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985, 28, 717.

6 Segal I and Walker AR. Low- fat intake with falling fibre intake commensurate with rarity of noninfective bowel disease in blacks in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa. Nutr Cancer. 1986, 8,186.

7 Kiguli-Malwadde E and Kasozi H. Diverticular disease of the colon in Kampala, Uganda. African Health Sciences. 2002, 2, 29.

8 National Statistics. Twentieth century mortality. 2003. CD ROM. ISBN 0 11 621665 4

9 Bender AE. Diet and killer diseases – evidence or opinion. In Rose J ed. Nutrition and Killer Diseases. 1982. Noyes, New Jersey. p8.

10 Talbot JM. Role of dietary fibre in diverticular disease and colon cancer. Fed Proc, 1981, 40, 2337

11 Connell AM. Wheat bran as an etiologic factor in certain diseases. Some second thoughts. J Am Diet Assoc. 1977, 71, 235.

12 Ornstein MH et al. Are fibre supplements really necessary in diverticular disease of the colon? A controlled clinical trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981, 282 (6273), 1353.

13 Cleave TL. The saccharine disease. CT Keats publishing Co 1975. Chapt 3, The saccharine disease and the colon. Available at http://journeytoforever.org/farm_library/Cleave

14 Hart AR et al. Beyond Burkitt-is diverticular disease more than just cereal fibre deficiency? Postgrad Med J. 2000, 76, 257

© Mary Griffiths 2007

Note This article appeared in the Incontact magazine Autumn issue 2007

Tags: bran, Constipation, Diarrhoea, Diet, epidemiology, Fibre